Most "ideology death counts" are worthless

this post will make half of y'all think I'm a tankie and half think I'm a neolib

Most "ideology death counts" are worthless

this post will make half of y'all think I'm a tankie and half think I'm a neolib

A deathcount (or "death toll") is an estimate of the number of people who died from an event, or under a government, or because of an ideology. Partisans of every flavor love to use deathcounts.

Many deathcounts are just political arguments by proxy: "[ideology X] caused [Y million] deaths -- how can you support [ideology X]?"

Used this way, deathcounts are a quick but powerful way to highlight the human cost of an ideology. In brief: Deathcounts are efficient propaganda.

This political utility encourages partisans to generate the highest possible estimates for their enemies. Unfortunately, that makes them nearly worthless for understanding the world.

This blogpost is a set of guides on how to construct better, historically useful deathcounts.

What's wrong with most deathcounts?

Most "death toll of X" infographics have three fundamental errors:

Weak sources: Bad deathcounts don't give sources, don't detail those sources, or trust low-quality sources on their face. For example, it's absurd to take the highest plausible death count as fact -- and most deathcounts do.

Excess aggregation: Bad deathcounts don't break down deaths by cause, time, or moral wrongness. For example, it's absurd to lump together deaths from execution and from bad policy -- and most deathcounts do.

Bad counterfactuals: Bad deathcounts simply equate {the number of deaths which actually occurred} with {the number of deaths caused by an ideology or policy}. That's bad causal analysis: The correct question is not "in reality, how many died?" (the actual) but "in a reasonable alternative world, how many less might have died?" (the counterfactual).

All of these are avoidable pitfalls. However, avoiding them require far, far more research than deathcounts usually get.

The rest of this article explains why these errors matter and how to avoid them.

In short: Most deathcounts don't morally disaggregate deaths, critically examine their sources, or compare to reasonable alternatives.

Three examples of overall bad deathcounts

Let's look at three examples of generally bad deathcounts.

Example 1: The reactionary Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation (VOC) was founded to repeat a deathcount: "100 years, 100 million killed". VOC rarely breaks down that number whatsoever -- but in 2016, they advertised the image below in Times Square:

Sources cited: None

Disaggregation: By country only

Counterfactuals: None

Example 2: The reactionary propaganda outlet Prager U often repeats the same line. In a 2017 video, Dennis Prager argued that communism should be "as hated as Nazism", and provided the graph below:

Sources cited: None

Disaggregation: By country only

Counterfactuals: None

Example 3: The reactionary propaganda outlet Turning Point USA (TPUSA) also repeats this number -- with Charlie Kirk offering the worst deathcount shown yet:

Sources cited: None

Disaggregation: By finger only

Counterfactuals: None

TPUSA, VOC, and Prager U all get their numbers the Black Book of Communism (BBOC), specifically from Stephane Courtois' introduction, which was very controversial. (For more details on why the intro is controversial, read my blogpost on the BBOC.) For a brief idea of why, take the Soviet Union's deathcount:

The BBOC's Soviet expert gave the deathcount as 15 million, which lumps together 4m "intentional" deaths with 11m famine deaths in 1921-22 and 1932-33.

Courtois adds 5 million for no reason, yielding 20 million (because Courtois wanted the total to be 100 million).

PragerU double-counts the 5 million 1932-33 famine deaths, yielding 25 million (because PragerU has no idea what the deathcount means).

VOC adds 10 million for no reason, yielding 30 million (because VOC has no idea what the deathcount means).

Charlie Kirk adds nothing to this discussion.

This example shows how bad deathcounts yield bad analysis: Partisan pundits usually don't care what the Big Number means (unless you spoonfeed the details to them), so they happily add extra deaths to make a Bigger Number. For example, VOC probably bumped 20 million up to 30 million so that the overall sum was 104 million (over 100), not 94 million (under 100).

Improvement #1: Credibility

or: cite your damn sources

Many popular deathcounts don't cite any sources or give any worthwhile details about the events they describe. They give you a Big Number, and you take it or leave it. All of the examples above have that problem.

Unfortunately, the fact that most deathcounts have terrible sourcing doesn't seem to have hurt their popular usage. I think this stems from weak popular understanding of how hard history is. History is complicated and society is messy, especially during the maelstroms of mass death.

(For those interested in getting an idea of how difficult it is to estimate historical deathcounts, I recommend Yang 1999. Even a massive, internationally-reported atrocity like the Rape of Nanking / Nanjing Incident has had a furious, 80-year dispute over where the deathcount lies, and recent estimates rely on about a dozen primary sources -- all for one event.)

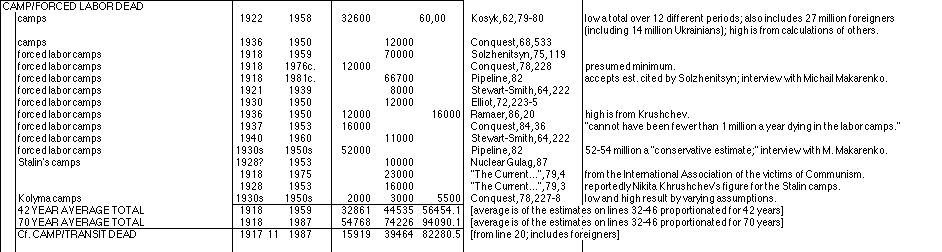

To understand why poor sourcing matters, consider Rummel 1990, "Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917". This is a widely-cited article by a famous historian, who claims that the Soviet Union killed 61.9 million people -- 40 million of which in labor camps:

In reality, nearly all modern historians estimate that about ~19 million people were ever imprisoned in Soviet forced labor camps, which killed about ~1.7 million people. (Or: The actual number imprisoned is about half of Rummel's number dead -- an absurdly, impossibly high estimate.)

Rummel's absurd numbers result from excessive trust in weak sources and selective sourcing. Below, I provide Rummel's table of estimates for deaths in forced-labor camps and their citations. Note that every single source Rummel uses are higher than 10 million dead ("10,000" thousands) for the Stalin period:

Rummel takes Soviet exile Aleksander Solzhenitsyn's testimony of 70 million dead (!) at face value (and counts them 2 times)

Rummel takes Soviet exile Mikhail Makarenko's testimony (to the US Senate) of 52-67 million dead (!) at face value (and counts them 2 times)

Rummel takes conservative historian Robert Conquest's estimates of ~12-20 million dead (!), themselves mostly based on exile testimony, at face value (and counts them 4 times)

and so on.

Rummel's table makes it clear why citing sources is not enough: One has to cite credible sources and justify their accuracy. (In particular, we should generally prefer sources with hard data over personal anecdotes.)

A common way of ensuring that one's sources are worthwhile is to cite critics of those sources and explain why their criticisms fail. The vast majority of death counts fail this goal -- they cite their preferred source and assume that that source is correct.

Rummel also fails this goal. Rummel rarely cites critical authors at all. In his book, Rummel cites authors with lower estimates just three times: Wheatcroft two times, Tottle one times, and Tauger zero times. Wheatcroft and Tottle are relegated to a footnote, which reads in full:

For opposing arguments, see Wheatcroft (1985, p. 134) and Tottle (1987), the latter an unabashed, book-length argumentum ad hominem.

Rummel simply dismisses these authors and doesn't bother to argue against their estimates.

In short: Good deathcounts are good scholarly works. They cite sources and explain in detail why those sources are correct.

Improvement #2: Disaggregation

or: tell us how people died and how evil that method was

We can make deathcounts more useful by changing their goal. Partisans often use deathcounts to argue "X killed Y people, so X is bad". Deathcounts cannot achieve this goal. There is no magic number above which ideologies are "bad" and below which "good".

Instead, detailed deathcounts should help identify the intentions and behaviors of an institution or ideology. The fact that Nazi Germany intentionally killed ~15-20 million non-combatants in 5 years tells us that Nazi ideology values civilian life very lowly.

Let's analogize. Theoretically, the purpose of criminal justice is to prevent and reform a person's harmful anti-social behavior. Categorizing behavior by severity and intention empowers that goal. Partly for this reason, many legal jurisdictions classify multiple categories of unlawful killing. For example, most US states follow categories like those below:

1st degree murder: A death caused by another person that [1] was pre-planned AND [2] did have malicious intent to kill -- "plotted to kill his ex"

2nd degree murder: A death caused by another person that [1] was not pre-planned BUT [2] did have malicious intent to kill -- "joined the barfight to stab his guts"

Voluntary manslaughter: A death caused by another person that [1] was not pre-planned BUT [2] did have non-malicious intent to kill BUT [3] did have special aggravating circumstances -- "killed him in the heat of passion"

Involuntary manslaughter: A death caused by another person that [1] was not pre-planned AND [2] did not have malicious intent to kill -- "crashed his car into them" (also: "criminal recklessness", "criminal endangerment", "criminal negligence", )

Natural causes: A death not caused by another person.

These are usually single deaths by single people, but scholars of mass death often make similar categories. For example, Wheatcroft 1996, "The scale and nature of German and Soviet repression and mass killings, 1930–45", notes the distinction between categories of repression:

The use of the word repression alone would imply that the events in the different countries at different times were uniform and in some aggregate sense comparable. I think that this would be mistaken. For a more detailed analysis we need to distinguish between different degrees of repression at different times.

We could begin with the temporary removal of civil liberties, pass through longer-term removal of civil liberties, including forced labour, and end with permanent removal of civil liberties by prematurely induced death. The latter could result from conscious action -- killing -- or from less conscious action -- placing the victims in a situation where they are more likely to starve, or die of diseases or exhaustion, or even of harsh disciplinary action. This would be equivalent to the distinction between murder and manslaughter, between purposive killing and death resulting from criminal neglect or irresponsibility.

This distinction between these categories of induced premature mortality is conventionally given great significance, although from the point of view of the victim the distinction may not appear all that great. [....]

Separating the question in this way leads us to ask whether we can get different quantitative indicators of (a) the different types of camps and places of detention, in terms of their scale and mortality rates, (b) the level of mass killings in terms of executions or direct murders, and (c) the mortality rate in similar repressive regimes in different social environments. Unfortunately, as we see, the prevalent currently accepted views on this matter do not always distinguish between these categories of repression and mass killing.

Both scholars like Wheatcroft and most legal systems categorize deaths in a spectrum from [most intentional] to [least intentional]. Following this tradition, I suggest the following four categories of mass death:

Mass Murder: An entity plans and executes a mass killing ("cleansing", "purge")

Mass Slaughter: An entity intentionally creates conditions that enable mass killing ("massacre", "terror")

Mass Endangerment: An entity knowingly creates conditions that cause much higher deathrates, which any reasonable person would expect ("repression", "forced labor")

Policy Failure: An entity creates conditions that cause higher deathrates, against that entity's own desires ("disaster", "catastrophe")

These categories are points on a spectrum with no hard boundaries. History is complicated and society is messy, especially during the maelstroms of mass death.

The fact that these boundaries are fuzzy helps to explain why labelling some historical events is so controversial. Consider the following atrocities:

The Holocaust is clearly murder (#1). Nazi Germany's leaders identified a group they wanted to kill, planned that killing, and killed them. (The Holocaust is one of the extremely few atrocities whose category is not debated.)

The Three Alls Policy is a combination of murder (#1) and slaughter (#2). Imperial Japan's commanders were ordered to "kill all, burn all, loot all" and to destroy "all males between the ages of fifteen and sixty whom we suspect to be enemies". This context birthed the Nanjing Massacre and other atrocities. (Japanese nationalists emphasize #2, most historians emphasize #1.)

Indian Removal is a combination of murder (#1), slaughter (#2), and endangerment (#3): The threat of genocide backed up mass removals (#1). American troops sanctioned mass violence by settler-colonial European civilians (#2). Any reasonable person would expect a thousand-mile forced migration to cause mass death (#3). (Nationalist American historians downplay #1 and #2, while revisionist American historians emphasize #1 and #2.)

Excess COVID mortality of 2019-23 in the United States is a combination of endangerment (#3) and failure (#4): For example, political leaders caused partisan distrust of vaccines, and low rates of vaccination caused ~318k deaths from 2021 Jan 01 to 2022 April 30. (Conservatives wrongly emphasize #4 and downplay virus severity, liberals correctly emphasize #3 and virus lethality.)

The Three-Year Famine is a combination of endangerment (#3) and failure (#4): Many Maoist Chinese policies, such as close planting, the Four Pests Campaign, and backyard furnaces, unintentionally worsened famine conditions. Systematic falsification of statistics yielded an "illusion of superabundance" in which regions "achieved" their unrealistic production targets by lying and hiding failures. The central government repeatedly decided to enact disastrous policies country-wide without bothering to test them locally and before building state capacity to monitor them. That decision falls somewhere between "endangerment" (#3) and "failure" (#4).

(Hundreds of books examine each topic above. Please don't take my short summaries as authoritative -- they're just intended to show the spectrum of intentionality of mass death.)

Why does this all matter? Focusing on the moral categories of death encourages us to highlight specific causes and responsible parties. That helps us partially avoid the problem of "sterile argument over body counts" highlighted by Yang 1999:

Worse, an obsession with figures reduces an atrocity to abstraction and serves to circumvent a critical examination of the causes of and responsibilities for these appalling atrocities.

When we break down the methods of mass death, we help explain why that mass death is horrifying -- and suggest who bears responsibility.

In short: When deathcounts (even briefly) explain the different moral categories of death involved, they must highlight causes of death and responsible actors, which better examines the behaviors of the ideology/institution involved.

A few examples of excessively aggregated deathcounts

To see why this spectrum of intentionality matters, let's look at two examples that flagrantly violates it.

Example 1: The vanguardist subreddit /r/CommunismMemes gave 940 upvotes to this infographic, which attributes 1.6 billion deaths to capitalism:

Sources cited: None

Disaggregation: By event (good!)

Counterfactuals: None

Factual errors aside, this infographic has no concept of moral categories:

It puts 12 million deaths from the Great Depression in America (deaths from starvation that didn't happen) in the same category as 1.5 million deaths from the Armenian genocide (organized murder and slaughter).

It puts "Post-Soviet Capitalism in Russia" (deaths from privation) in the same category as the Herero and Namaqua genocide (organized murder and slaughter, #1 and #2).

It puts 306 million deaths from cigarettes, worldwide, 1960-2011 (deaths from addiction) in the same category as the Nazi Holocaust (organized murder, #1).

These conflations are crass. They're also absurd. Grouping policy failures (of austerity, shock therapy, and public health) with organized mass violence doesn't advance anyone's understanding of mass violence under capitalism. It just produces a Big Number.

Counterexample: Now let's look at a counterexample. The vanguardist-leaning socialist subreddit /r/LateStageCapitalism gave 5000 upvotes to this infographic, which attributes 20 million deaths per year to capitalism:

Sources cited: Links (good!) to whole websites (bad!)

Disaggregation: By cause of death (good!)

Counterfactuals: None

This is one of the best deathcounts shown here. It provides sources (though it should be far more specific). It provides specific causes of death (which help one understand how poverty causes death). And those causes of death are of similar moral categories (deaths of deprivation, #4).

That leaves just one route of attack left: Critique the counterfactual. (For some analysis of this meme in that context, see "Why counterfactuals are good: Poverty, death, neoliberalism, and socialism".)

Improvement #3: Counterfactuals

or: mass killing is avoidable, actually

We can make deathcounts more useful by changing their goal once more. Bad deathcounts simply equate {the number of deaths which actually occurred} with {the number of deaths caused by an ideology or policy}. That's bad causal analysis: The correct question is not "in reality, how many died?" (the actual) but "in a reasonable alternative world, how many less might have died?" (the counterfactual).

Put another way: Bad deathcounts simply ask, "How many died?" Good deathcounts should ask, "How many could have been saved?"

For example: Official records show that about 1.7 million people died in Soviet forced-labor camps (often called "gulags"). Most deathcounts take this "actual" number as the number of deaths caused by Soviet forced labor camps.

But that's wrong: If Stalin's authoritarian mass incarceration (the actual) had never happened, those gulag inmates would've been civilians (the counterfactual). Civilians died at rates between ~1 and ~4 times lower than gulag inmates. Simplistically, the number of deaths caused is equal to:

([death rate of gulag prisoners] - [death rate of comparable civilians]) * [number of gulag prisoners], or

[excess death rate from gulags] * [number of gulag prisoners], or

[excess death count of gulag prisoners]

The goal of this exercise isn't to downplay Stalinist crimes (or whatever atrocity we're examining), but to highlight exactly how much worse they made people's lives. Put another way:

We aren't asking "How many people died under Stalin's rule?"

We are asking: "How many people did Stalin's rule kill?"

The latter is a far stronger indictment, because those deaths were avoidable. Those deaths are on Stalin's hands alone. That's why counterfactuals matter.

In short: Good deathcounts should attempt to highlight avoidable deaths, which need not have occurred in a plausible counterfactual world.

Conclusions and shilling

In short: Good deathcounts should morally disaggregate deaths, critically examine their sources, or and consider avoidable deaths.

Why did I bother to write all of this?

Because deathcounts, for all their easy flaws, can be extremely useful tools to more deeply understand the world. Having a number for something -- "6 million executed", "4 million starved" -- really helps people understand the scope of historical horrors.

Most "socialism death toll" and "capitalism death count" posts are terrible. I've long wanted to compile my own deathcounts which use stronger citations, which highlight different categories of death, which consider counterfactual death rates. This blogpost is helps formalize the bases on which I judge other deathcounts, and my own efforts.

I'm writing blogs on socialist and progressive topics. To support my work:

Subscribe on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/socdoneleft

Subscribe on Substack:

Deaths counts have killed 20 million people.

Do you have any good examples of deathcounts that include counterfactuals?

IIRC, the Stalins death count post you made on Twitter (that I quite like) doesn't include counterfactuals